KARAMBITS & MAGIC SWORDS (Crazy Eddie stories part 1)

“Smell the blade.” said my Indonesian Penchak Silat instructor, Suryadi “Crazy Eddie” Jafri.

“Why?” I replied, not understanding what this had to do with the question I had asked him.

“Billy, just smell the blade.”

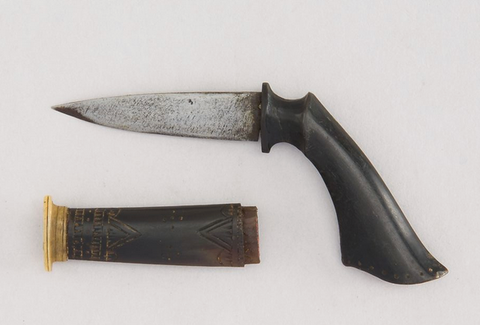

Eddie had given me a small Indonesian knife, with a pistol grip and a 3 inch, leaf shaped blade of black damascus steel. It had a strange, elongated hole that looked to be deliberately forged into the center of the blade. The whole thing was small enough to fit into the palm of my hand.

When I asked him why the hole was there, he had given me that strange instruction about smelling the blade. Like the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, both Eddie and my main instructor Tuhon Leo Gaje, would often answer a question with another question; hoping to inspire deeper thought on a subject.

So I smelled the blade and found that it smelled like flowers.

“It smells like flowers, Eddie. Why?”

“It was dipped in perfume.”

“OK, but why? What does that have to do with the hole?”

Finally relenting, Eddie told me that the hole is meant to hold poison. Wax was put on either side of the hole to hold the poison in place. When the knife was stabbed into a person, the pistol grip was to be twisted, breaking the wax and releasing the poison.

The perfume was there to mask the smell of the poison, so that when the village medicine man came to examine the victim and would sniff the wound, he would not be able to figure out what poison was used and therefore could not decide which antidote to give the unfortunate victim.

An Indonesian Badek knife, similar to Eddie's (but without the hole forged into the blade).

I often tell this story whenever I teach a Silat class, just to give the students some idea of the kind of thinking that went into the art they are about to learn.

I spent five years in the late 1970’s and early 80’s cross training with Eddie Jafri, (in addition to my Pekiti-Tirsia training), and remember several “interesting” conversations like this.

During the few times people convince me to teach Karambit, I like to begin with my own Socratic question:

“Do you know how to tell which scorpion has a deadly venom and which is merely painful?”

I tell the students it’s not the size of the stinger that matters, it’s the size of the claws. There is actually an inverse relationship between the size of a scorpion’s claws and the power of the venom. When you see a scorpion with large, strong claws; that is its major weapon and it will subdue its prey with its claws. The sting of this kind of scorpion is painful but not deadly to a human. However, when you see a scorpion armed with small, little claws, it uses the powerful venom in its stinger to both subdue its prey and defend itself and this is the kind that can kill you.

The reason I tell these stories before a Karambit class is because of the size of the Karambit I was taught with. Eddie’s Karambits were relatively small, with blades around two inches long. This left you with only an inch to an inch and a half of usable blade length (and the karambits designed to be concealed in a woman's hair, as an anti-rape weapon, were even smaller). Yes, you wouldn’t want to get cut by them, but unless you were very precise with your first cut, they would not stop a determined armed attacker before he could do some damage back with his own blade.

The idea of Eddie’s training was that you are attacked in anger by an opponent who is not displaying a blade, but probably has one concealed on his person. In Eddie’s culture it was not “cheating” to pull a weapon on an unarmed opponent, it simply means that you managed to draw your blade first. This is one of the reasons you often see Penchak Silat fighters “tap” their training partner’s sash or belt area in class. They are doing a quick frisk to try and locate the opponent’s blade before it gets drawn.

Most of the Karambit techniques I learned from Eddie shared these traits:

The opponent was unarmed (or at least his weapon was not in his hand).

The opponent was cut in the midst of a lock, throw or takedown.

The techniques would work much better if the little “stinger” had some “venom” on it.

The techniques were difficult to do “knife vs knife.” This is one of the reasons Eddie liked Pekiti-Tirsia knife work more than his own Silat and also one of the reasons Tuhon Gaje did not like the Karambit as a fighting knife.

I did not see Filipino martial arts instructors use a Karambit until this century (and specifically after the advent of YouTube around 2005). When they did use them, they were much larger than the blades Eddie Jafri had used. That’s an important point. If you don’t have poison on your blade, would you rather defend yourself with a 2 inch blade or a 6 inch blade?

In most parts of the western world, a knife is illegal to carry if the blade is OVER a certain size.

In many of the countries where the Karambit comes from, it is illegal to carry a blade UNDER a certain size. Why? Because a small blade is a concealable blade and can be taken surreptitiously into places where blades are forbidden, (especially prior to the invention of metal detectors). I remember a story about a policeman in Malaysia who saw a young man walking in an odd way. When he searched the young man he found a Karambit concealed in his sandal, (in the police station, the young man confessed that he was on his way to kill someone who had insulted him).

People all around the world who grow grains such as rice or wheat, or hay for animal feed, will use some type of tool with a curved blade for the harvest. Whether its the kama in Japan, the scythe or sickle in Europe or the Karambit in Indonesia; most people who use these tools will also have a way to fight with them. I look at this as similar to a carpenter learning how to fight with a hammer. It’s not the best weapon design there is, it’s just a good idea to know how to use the tools you have on you in case you are attacked by surprise.

Some things to think about:

1. EASY TO KILL, BUT HARD TO STOP. Humans may be relatively easy to kill (compared to larger and stronger animals), but they can be incredibly hard to stop before they can deliver one final cut or stab. Do a search on YouTube or Google Images for “Knife Wounds”, “Knife Fight” or “Machete Fight” and you will see people taking some amazing damage and not going down right away. When looking through the Google images, pay particular attention to those people who are sitting up or standing, despite having multiple stab wounds or deep lacerations.

2. SIZE DOES MATTER. A knife is not a sword. Most of the knife wounds you will see on YouTube or Google are from blades that would have been considered too small for combat on battlefields when swords were the main close quarters weapon.

3. TEST IN SPARRING. If you spar with a Karmbit trainer (with proper protective gear for the job), you will find that while it is good offensively, especially against an unarmed opponent, it is more difficult to use counter-offensively against an armed opponent than when you are using a straight blade.

What are the pros and cons of a Karambit?

Pros:

1. It looks intimidating. This shouldn’t be discounted as a small thing. Especially if your goal is to scare a bad guy away without having to fight him. This is a good goal to have for anyone, but especially useful when a female is accosted by a larger, stronger, but unarmed, male attacker. Most men who would attack a woman are cowards; so seeing a woman they thought was unarmed and an easy target suddenly pull out a wicked looking, curved blade will usually make them back off and give the woman the distance they need to escape. (This male attack on a female scenario is exactly the one that would justify the use of a knife against an unarmed attacker in many jurisdictions).

2. A single edged Karambit* cuts best on a forward motion; an instinctive defensive motion that’s close enough to a punch or push that beginners can understand its use quickly.

3. The curve of the blade helps it capture tendons, muscles and blood vessels during the cut, which can help it do more damage than a straight blade of the same length, when cutting to the same depth.

4. The ring on the grip adds in weapon retention. Note* Karambit means “Tiger Claw” and it is the curve of the blade, (shaped like a tiger’s claw) and not the ring on the grip, that traditionally defines this knife.

5. Because you are leading with the point when using a Karambit, you get a combination cut and thrust which penetrates deeply.

Cons:

1. It looks intimidating. Yes, this can also be a con. Even if the laws in your area do not prohibit the carrying of a Karambit, its fame (or infamy) as a dangerous “fighting knife” means that you will have an uphill battle convincing a judge or jury that you did not intend to go looking for trouble when you decided to carry that blade.

2. *Traditionally, Karambits in S.E. Asia are double edged and most Silat techniques with the weapon are built upon that design feature. Therefore, many parts of tradistional techniques do not work well for use with a single edged blade.

3. While a pushing motion is instinctive for most people when facing danger, it is often a pulling motion that helps the most in capturing the opponent’s weapon arm in order to control it. Yes, there are Karambits that can be used to catch and pull the opponent’s arm; but these have large barbs built into the back of the blade. These barbs can also get stuck in an opponent’s clothing or body on a thrust, much the same way a barb on a fish hook will get stuck in a fish. This may mean that your weapon gets stuck in your opponent: which can be a problem if he doesn’t go down right away or if you are fighting more than one person.

4. The curve of the karambit blade helps it capture anything in it's path, including clothing, which can bunch up and stop the cutting action of the blade. This is especially true if your area has cold winters that require thick clothing. (Which is not the case for S.E. Asia; where the karambit and the techniques for its use originated).

5. While the ring aids in weapon retention, it also means that the ring can dig into your finger if the blade gets stuck in something (such as a bone or heavy clothing). This has the potentcial to do severe damage to your finger. Think about delivering a full force cut into a target and the blade of your karambit suddenly gets stuck partway through the motion. If the handle slips in your grip, all that force is transferred into the small surface area of the ring on the side of your finger. Try this experiment. Take a foot long loop of paracord and place one end over your hand and the other on a fixed object and then gradually pull against it at the same angle you would when cutting with a Karambit. You will then get some idea of how much force can be transferred to the side of one of your fingers if your blade gets stuck during a fight. If you train with a real Karambit against resistive target materials like rolled carpet, bundles of clothing or even stacked cardboard, you will only make this mistake once. If you are lucky you just break the skin a bit. If you are unlucky, you can break a bone or dislocate the finger (especially if the ring slips down the finger to the second knuckle and gets pulled with more leverage than the joint can handle).

6. Because you are leading with the point when using a Karambit, you get a combination cut and thrust which penetrates deeply; sometimes deep enough that the point will get stuck in bone. Yes, a straight knife can get stuck too, but the distance between the point of the Karambit and the center of your grip means that there is a lot of leverage on the tip if you try to get the blade out using a twisting motion. This is good if you have a thick blade imbedded in a thin bone; in which case the blade may win and the bone may break. This is bad if you have a thin blade imbedded in a thick bone; in which case the bone may win and the blade may break.

7. While a straight line is the shortest distance between two points, it also has the longer reach. Let me explain. In the photo that leads this article you see two knives. The straight blade is a Mora Robust Pro with a 3.6 inch blade. The aluminum Karambit trainer has a blade just over that length if you measure it along the outside of the curve and just under that length if you measure it on the inside of the curve. Both knives are held with the blade exiting from the bottom of the fist. Held this way the Karambit may be used with the same motions as a straight punch, uppercut or a hook. The straight knife in icepick grip can be used in a similar motion to a hammer fist. Notice that it is only the part of the Karambit blade that extends past the front of the fist that will penetrate, as you loose some blade length as it curves around the small finger to face forward. Meanwhile, the straight blade has its entire length available for use. Both knives have roughly 3.6 inch blades, but which type has more usable length?

More things to think about:

Most of the Silat techniques I learned were with a Karambit held in icepick grip and used much like a MMA fighter would use a punch; to stun an opponent right before a takedown, throw or lock. (Remember, in Eddie’s culture, the lock was probably there to give the poison time to take effect, not to hold the opponent under control while waiting for the police to arrive). These techniques were easy to do when fighting an unarmed opponent, but were much more difficult to use as stop-hits directly on the weapon arm, as I did when using a straight training knife during knife sparring in Pekiti-Tirsia.

Your counter cuts with a Karambit are often intercepting the opponent’s weapon arm at an oblique angle, instead of a direct hit, as you would with a straight blade. Again, I’m not saying this is bad, just more difficult to do under stress. Capturing an opponent’s arm with a straight blade is more natural when using a knife in icepick grip than it is with a similar sized Karambit. Yes, there are Karambits built with barbs on the back to help capture and control an arm during a pulling motion, but when used after a stab, these barbs can act like the barbs on a fish hook and anchor the blade in place, making it difficult to pull the blade out quickly. This is not a problem if you are in a duel with a single opponent in the jungles of Indonesia and are relying on the poison on your blade to get the job done, (and in that culture, “getting the job done” may include the pyrrhic satisfaction that your opponent will die soon after you do). However, getting your blade stuck in an opponent may be a problem if you are trying to use the knife to escape multiple bad guys and get home safely to your family.

When using a Karambit in hammer grip you do have a natural motion in your cuts (very much like cutting with a straight blade in this grip). However, you still run the risk of getting hung up in bone or clothing, since most of the movements with a Karambit combine both a cut with the edge and a thrust with the point. When using a knife with a straight blade in hammer grip, your cuts are much more likely to slide off a bone than get stuck in it.

Superman vs Batman:

I have a saying, “Everyone wants to learn how to fight from a Superman and they want to buy a magic sword -- when what they should be doing is learn how to fight from a Batman and go buy a Glock.” (and spend the money you saved by not buying a magic sword to get good training on how to use the Glock - otherwise it becomes just another "magic sword").

The hype surrounding the Karambit in recent years reminds me of the similar reaction that occurred when Bruce Lee used nunchucks in “Enter the Dragon” in 1973. What was once a common farm tool used in traditional martial arts as a weapon of necessity, because they couldn’t carry something better, became the supreme and deadly weapon of “martial art killers” (at least in the minds of law makers of the time, who decided that they had to ban a rice thresher to keep the public safe).

I call this type of thinking the “Magic Sword Syndrome.” This is when a weapon becomes popular because of the skills of the famous person who uses it and then some people begin thinking that if they get a similar weapon they will magically acquire the same skills as the guys who trained with it for many years.

You see this whenever a hero in a blockbuster movie has a favorite weapon (Dirty Harry’s 44 Magnum, Indiana Jones’ bullwhip), or when a military unit gets famous (such as the Ghukas with their Khukuri or the many knives of the Navy Seals.

These days you are seeing this same infatuation with the Karambit because of internet videos showing martial arts instructors using them in fast and flashy demonstrations that amaze those unfamiliar with the weapon, without showing the years of training needed to get the speed and precision required to make the techniques work or understanding the specific environment and circumstances that the weapon was intended for.

Finally, I don’t want you to think I am totally against the Karambit. It has its use in specific circumstances. I just don’t want you to think of it as a “Magic Sword.”

Basic training for the Cimande Silat punch.

Here are two empty hand versions of the karambit techniques I learned, to give you an idea of how this tool was used.

Train hard, but train smart.

Tuhon Bill McGrath

For information on upcoming Pekiti-Tirsia classes, seminars and camps, visit:

https://pekiti.com/pages/upcoming-seminars

My recommended karambit trainer, from Vulpes Training:

COPYRIGHT 2018

WILLIAM R. MCGRATH